Building a Strong Vaccine Infrastructure

It’s officially flu season here in Richmond. A century ago, that was a terrifying statement; back in 1918, when we didn’t have a flu vaccine, a worldwide flu pandemic killed up to 100 million people. We’ve made a lot of progress since then, but 50,000 adults in the United States still die every year from vaccine-preventable diseases such as the flu, pneumococcal pneumonia, and pertussis. Thousands more suffer serious health problems—costing our healthcare system billions of dollars—which immunizations can prevent.

We’re a whole lot better off today compared to one hundred years ago thanks to amazing scientific advances, but even the best vaccines are ineffective if they don’t reach people. As a nation, we’re failing to get them into the hands of the adults who need them most—largely because patients encounter confusing health information, do not know where to go to access evidence-based information about recommended vaccines and experience too many barriers to access. These obstacles are especially difficult to manage for poor, at-risk, chronically ill and minority and ethnic populations. Unless we quickly and substantially improve access to and use of vaccines, the negative health effects of vaccine-preventable diseases will only worsen.

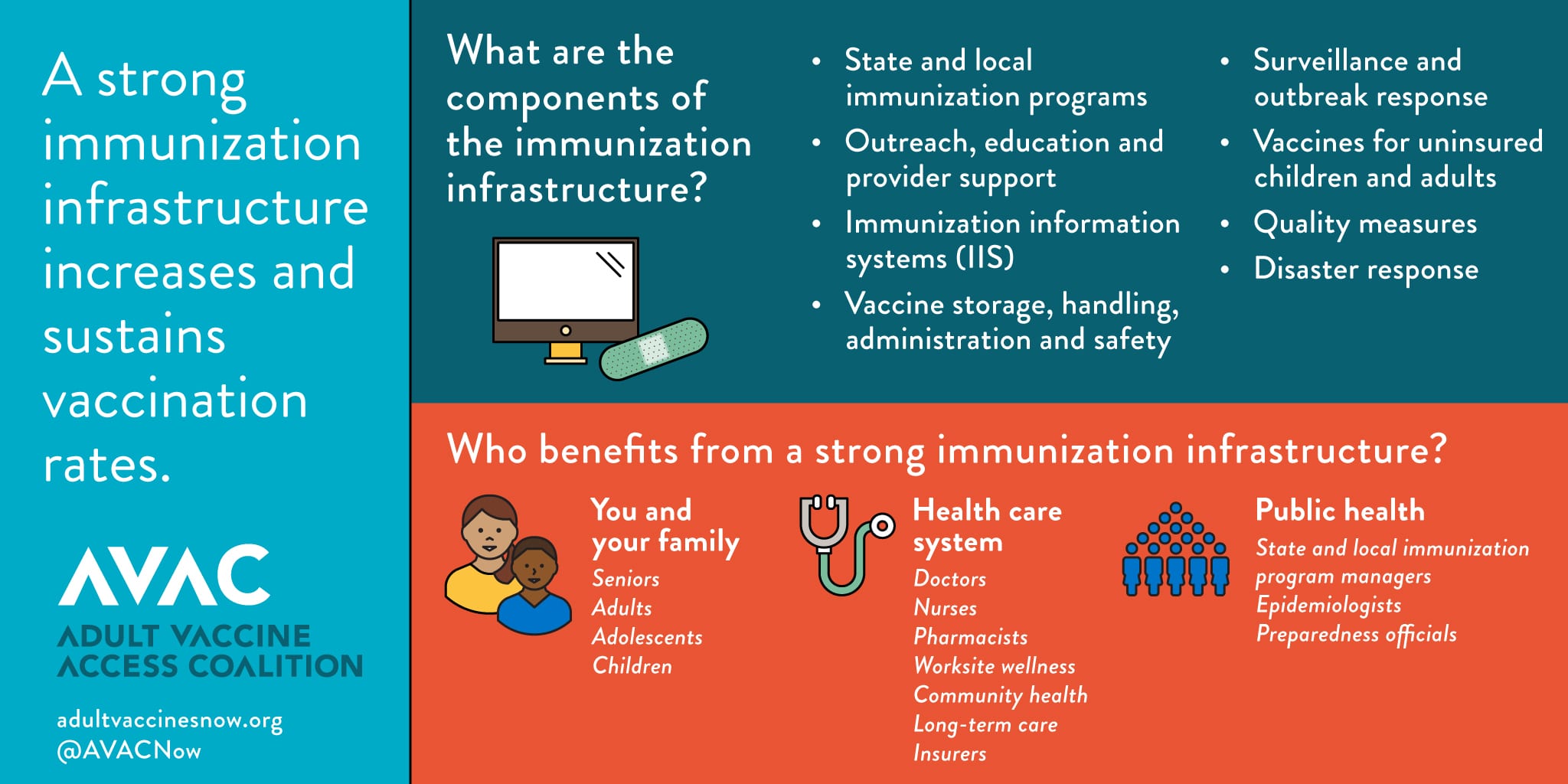

A strong vaccine infrastructure is critical to increasing and sustaining vaccination rates. Similar to transportation infrastructure—which requires a well-connected network of roads, bridges, tunnels, and mass transit to get people and products where they need to go—a vaccine infrastructure relies on a series of components that must work seamlessly together: well-funded state and local immunization programs, robust immunization information systems, proper vaccine storage and handling procedures, well-oiled disaster and outbreak response, provider education and support, and immunizations for the uninsured.

Here in Richmond, Bon Secours Health System illustrates the power of a thriving vaccine infrastructure. A systematic education and awareness campaign plan to encourage Medicare beneficiaries to receive their annual wellness visits led to those beneficiaries receiving a 40 percent higher number of pneumococcal vaccines administered than those beneficiaries not receiving an annual wellness visit. Our mobile Care-A-Van has delivered more than 6,000 vaccines to uninsured people right in their own neighborhoods. We even use phone apps that let patients know when it’s time to come in for their vaccines.

During flu season, we take care of our own house first by requiring our 40,000 employees, contracted providers, and other personnel to all receive the flu vaccine or wear a mask for the duration of flu season. With respect to our patients, our nurses screen the flu vaccine status of all inpatients upon admission; if patients are eligible, an alert appears in the patient’s electronic health records, which automatically orders a vaccine that can be given prior to discharge. We also offer free flu shots at our free-standing emergency room, at our hospitals and medical centers.

Taking these steps required buy-in from physicians, nurses, staff, administrators, and even our patients. It’s multi-layered, complicated and there are a lot of moving parts, but it’s also absolutely necessary—not only for ourselves and our families, but for our health care system and the city many are proud to call home. If a terrible flu pandemic hit Virginia today, we’d be well-positioned to make sure vaccines could get to every single person who needs them, and fast.

Local innovation is driving change on the ground in Richmond and in other communities, but we can’t do it alone; the federal government must do its part to ensure that we have the funding and technical support necessary to do our jobs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Section 317 program funds state and local health departments to carry out a variety of vaccine-related activities, providing essential grants for the purchase of vaccines, safety and effectiveness studies, education and outreach, and implementation of evidence-based community interventions to increase coverage. Unfortunately, the Section 317 program is facing a $50 million funding cut. We need to maintain full funding for Section 317 and further ensure full implementation of the National Adult Immunization Plan to raise adult immunization rates to much higher levels.

Getting a vaccine from the lab to a patient’s arm is no sure thing. Too often, this is much more complicated than it needs to be. But if Washington D.C. can work hand in hand with communities like Richmond to strengthen our vaccine infrastructure, the next 100 years will be even more remarkable than the last.

Liana Orsolini, PhD, RN, ANEF, FAAN, is a corporate nurse executive with Bon Secours Health System Inc. in Virginia